I raised the expectation,

You shook your head sadly.

Like fish in water and fowl in the air

It’s not easy to meet…

I saw you off on your way

And felt hundreds of jumbled feelings.

—Nguyen Binh

(1918-1966)

For years I had loved the words “Perfume River.” I imagined sailing down this Vietnam waterway of which I knew nothing. I imagined it smelled gorgeous and the experience would be one of romance and poetry. That’s why on my single day in Hue, the ancient, imperial capital of Vietnam, the first thing I did was to inquire how to take a boat ride on the Perfume River.

Since I had only a day, I needed a short boat ride as I was keen on seeing the famous Imperial City, the 14th century walled palace complex, in the afternoon. “No problem,” said the girl at the hotel desk. She told me she would arrange a taxi pickup for me in the morning to one of the dragon boats that provide voyages on the river. The boats, shaped and painted like dragons are designed for tourists. They stop at the main sites along the riverbank so you can hop on and off and they wait for you. Since I didn’t have much time, she suggested I go directly to the Thien Mu pagoda and get a taste… or rather a whiff of the Perfume River, then return to Hue.

When I got to the dock I found a boat waiting for me and soon realized I was to be the only passenger. “Hallo Lady!” A thin, aged woman working on the boat, called to me. She reached out to hold my arm and steady me as I jumped aboard the wobbly craft. She then bade me sit in a white plastic chair on the deck. Most of the dragon boats looked grand with two great dragon heads at the prow. This boat had only one dragon head. Like the woman, it was small and weathered but I had complete confidence in its safety because the pilot, a silent, middle-aged man looked steady.

With a long wooden pole, the woman, agile as a child, pushed the boat away from the shore. The engine rumbled to a start and off I sailed down the Perfume River.

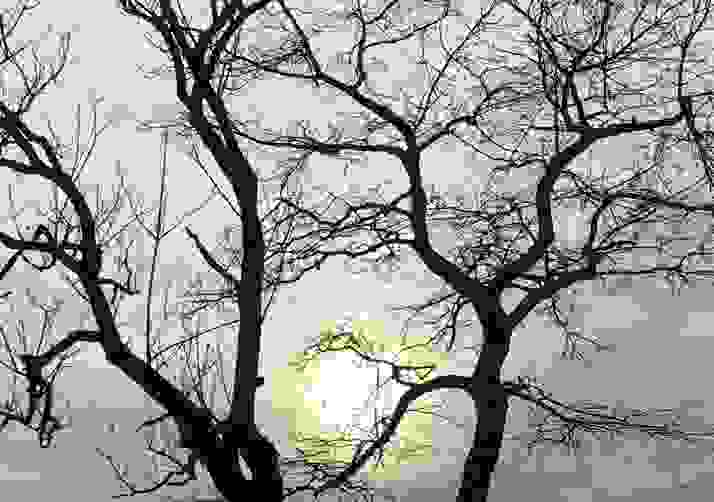

The river gets its name from the fragrant scent of the blossoms from nearby orchards, that in autumn, float along the water. In autumn, the river must seem poetic but now in winter, the wide slow river was as gray as dust and the only fragrance I smelled was engine fuel.

I sat back and relaxed, watching other dragon boats chug past under the cloudy sky.

As soon as our journey was underway, the boat woman got busy. She unrolled a bamboo mat on the damp floorboards, went back into the small dim room— the only room on the boat—and emerged with a Styrofoam cooler of soft drinks for sale. I bought a can of Coke and the selling continued. The woman, toothless as a toddler, must have made at least eight trips back and forth into the room to present each time a different array of wares: silk pajamas, embroidered cloth bags, fresh water pearl earrings, horn bracelets, agate necklaces, key chains and sets of chopsticks, each charmingly tucked into a silk case. She spoke little English but enough to be tireless in her effort to sell. Each time she brought out something new, I shook my head regretfully to show I was not at all interested, but after a short while, seeing her look so very disheartened, I relented and bought a package of chopsticks. At this sale, she perked up and gave me a bottle of water in gratitude.

I couldn’t see much life from the boat as the riverbank was hidden in thick foliage so I became curious about the woman. I stole glances at her as she moved about. Her own stolen glances at me revealed she was equally curious. Now and then we smiled at each other but made no attempt to converse.

After an hour or so we came to the Thien Mu (Celestial Lady) Pagoda. I jumped off the boat onto the sandbank and walked up the hill path, through the small pine forest to the pagoda. Built in 1601, it is the oldest religious structure in Vietnam and the crown of the Buddhist monastery surrounding it. The pale pink tower of the pagoda rises gracefully seven stories high, each story representing another stage of enlightenment.

The garden of the monastery surrounds the pagoda and you can enter a temple where a bored-looking boy, about ten years old, beats a large gong. The pagoda and the grounds of the monastery exude peace. Yet this most tranquil place was a center for anti-government fervor during the early 60s. The tourists who jostle to take a photo of the 1950s Austin motorcar attest to the monastery’s eerie history of protest. It was here in 1963 that one of the monastery’s monks, Thich Quang Duc, drove the Austin to Saigon where he set himself afire in protest at the Catholic President Diem’s persecution of Buddhists.

Sobered by my visit to the monastery, I returned to the boat and we headed upstream, back to Hue. I was gratified that on the journey back, the boat woman didn’t try to sell me anything. Like all Vietnamese, she was curious about a woman travelling alone and she began to ask me questions. We started to communicate with hand gestures and three-word sentences. I told her I was from America, that I had flown here from Hanoi and the next day I would be going over the Marble Mountains to Hoi An. I told her my name and she told me her name was Hung, which I later learned means pink rose. With a hint of pride, she told me how old she was: sixty-five.

She asked my age and I told her.

We were the same age.

The knowledge stunned us both into silence… and melancholy. For in that moment our light-hearted reaching toward each other, turned poignant. Though the same age, my life was privileged. I was on vacation, overfed, with a full set of teeth, smiling, carefree, enjoying the freedom that comes with having leisure time and credit cards. She was still doing hard physical labor and struggling to sell trinkets to one passenger and I sensed, struggling with something else.

The speed at which her smile vanished on realizing we were both sixty-five, told me she too had felt the cruel disparity. For the rest of the ride, she no longer smiled.

When we did speak again, I learned she had been married when she was seventeen. She had loved her husband since she was a little girl and after they married, she bore seven children. One was her son, the dragon boat pilot with whom she now lived in the dark boat room. She had never left Hue. Ever.

As she spoke, I did the grim math.

She and I were nineteen years old in January of 1968. While I was in college, acting in plays and preparing for a fun-filled summer in Israel and Greece, she was a young mother in Hell. In January 1968 during the “Tet Offensive,” to take back control of the south, the Viet Cong captured Hue, set up a provisional Communist government and murdered thousands of civilians they thought were South Vietnam sympathizers. Nearly 3000 men, women and children were tortured, executed then thrown into mass graves. Another 2000 went missing. One hundred thousand residents lost their homes and no one in the city could have escaped the tragedy. After three weeks, the city lay in ruins and corpses lay everywhere. This was the infamous “Massacre at Hue.”

“Come,” the woman beckoned and I followed her into the cramped, shadowy room. The room was painted mint green and was sparsely furnished: two more white plastic chairs, a television, a cooler for drinks and some benches on which bedding was piled. In the corner, rose stacks of cardboard boxes filled with her tourist wares. She walked over to a large, framed black and white photograph on the wall, pointed to it then pointed to herself.

“Me,” she said. “Marry.”

I looked up at the photo to see the face of pretty, teenage girl, an innocent bride.

“Beautiful.” I said. She understood this word and nodded.

“And your children?” I asked.

“No more,” she said quietly. “No more here. No more now.” She pointed to her son whose back was facing us as he piloted the boat. “One boy. No more now.”

She didn’t have the words to tell me more; I didn’t have the words to ask her more. And, even if we shared the same language, we would have had no words that could matter.

No more now.

We docked in Hue, she helped me climb out of the boat and I waved goodbye to her. She stood at the prow waving back to me and she stayed waving to me much too long.

As the boat sailed away up the Perfume River, the figure of the woman shrunk smaller and it is that miniature waving image of her that haunts. Not because my last view of her was at such a great distance, but because my full understanding of her—what she lived through and how— was at such a great distance, forever impossible for me to justly breach.